from section ii

Learning and Working

Chapter 1: Setting Out

There was a time in my early teens when I wanted to be a composer. I had a passion for the pop charts. In addition to the Beatles and Radio Luxembourg, I discovered Grieg, Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, Stravinsky, Shostakovich, and Mahler—in that order. Each created moods and emotions during a time when such things seemed to be the essence of life.

I wasn’t exactly talented enough to succeed in a musical career. And, unfortunately, you could not study art and science simultaneously in our school system, so I had to make a choice and move away from arts towards the sciences where I would get better grades. A painful choice and one that I would love not have had to make. I now know that the ability to bring science and art together in anything you do brings the greatest rewards.

Every Saturday morning I visited the local library in Epsom, Surrey. Amongst books on architecture I found books on town planning. I was fascinated to see that cities could be planned, and I started to imagine how I would alter places that I knew, like London or Epsom.

Big changes were soon to hit the area where I lived, with plans to build the M25 London Orbital Motorway just three or four miles away from my home. I found a map of the proposed route and spent my Sundays walking and photographing the local scenery prior to construction. I recorded the rivers, woods, and open land that would be lost. I felt torn between the savagery of the destruction to come and the benefits we would experience once we could move around London so freely. The road was going to change millions of lives and the way we would think about London. But it would destroy the natural beauty of an area I loved.

I passed the entrance exam for Cambridge and had a gap of nine months before I could start. I applied to several civil engineering consultancies for a short-term job and chose a placement at Ove Arup on Fitzroy Street in London. Ove Arup was a well-known firm. I was excited about working with them for a few months because they were the engineers for the Sydney Opera House.

I joined Ted’s team where I worked for a super engineer called Ian Liddell. The project was the Bundesgartenschau Multihalle in Mannheim, West Germany. Frei Otto was the architect. Doors were opening. I had found the mentors I was looking for and was about to work on one of the most amazing projects imaginable.

Frei Otto was an architect and an engineer. He always worked with members of both professions to achieve results. Based in Stuttgart, West Germany, Frei ran a research and teaching institute of lightweight structures. At the time he was already known for his incredible design achievement of the Olympic Complex in Munich, 1972. His buildings were inspired by nature; they aimed to work with nature rather than against it. The building’s form had to be defined before it could be tested and built. Before computers had become commonplace, physical models were essential to discover and define form. Soap films would be stretched between wires to define tension structures; hanging chain models were made to define forms for compression structures. For the Mannheim grid-shell, Frei had already defined a form using a hanging chain model.

Ted’s team at Ove Arup had modelled a compression shell using perspex strips. My job was to hang nails onto the model and measure the deflections. This was how we predicted when the shell would buckle. More and more nails were added across the whole surface. It was exciting as the shell became more and more like a jelly, sensitive to the slightest touch. These physical models made me aware of how you can feel changes in a structure as it approaches collapsing. This experience has stuck with me to this day.

This period offered an amazing experience that gave me a springboard into engineering. I remember hearing one of the engineers whistling Mozart. As he walked across the room I thought, this is another world that I didn’t know existed!

At age eighteen I was seeing that things were going to get a lot better after school. And, I had some money in my pocket.

I studied engineering for three years at Cambridge. My memories are mostly of cold, windy days, studying things that were not at all inspiring. We learned methods and equations that I found dull and difficult. I was not interested in engineering in the way that they talked about it, and began to think I had made a mistake and wasn’t cut out to be an engineer.

My career took a slightly different path. One evening in the spring of 1976 I had a message from the porter’s lodge to call Ian Liddell, my boss from Ove Arup. Ian told me that Ted and the team had set up a new practice called Buro Happold. They were moving to Bath in the west of England, where Ted would be the head of the School of Architecture and Building Engineering at the University of Bath. The practice started on the first of May, 1976. I went there as soon as the university let us out on holiday to spend the long, hot summer of ’76 in Bath. We all (the whole office) slept on the floors in Ian’s new house, along with two squeaking guinea pigs. Most evenings we drank at the Assembly Inn and helped Ian upgrade his beautiful but tired Georgian terraced house after dinner.

I worked on a project for Riyadh, in KSA, that included a fantastic domed roof structure inspired, as with the Mannheim grid-shell roof, by Frei Otto. My role was again to hang nails on an acrylic model and predict buckling failure loads. Having assumed that the Mannheim challenge was a one-off, here was another already - it confirmed that these engineers I was getting to know could be relied on to give me challenges and let me explore the unexpected.

Chapter 2: Starting Work

Once I graduated in 1977, I went straight to join Buro Happold in Bath. But after just two weeks, Ted Happold came and asked me to become a researcher in his university program. He was setting up a research group into air-supported structures, and the funds had recently been agreed upon through the Wolfson Foundation.

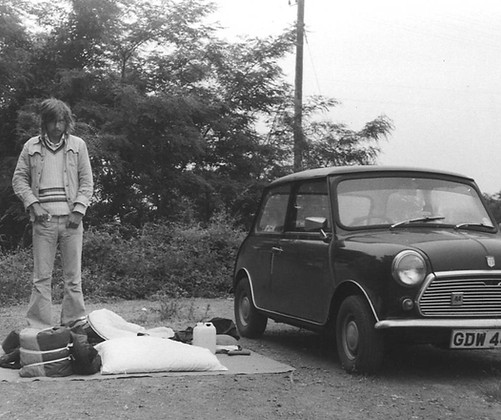

In my first year, Ted asked me to drive around Europe to examine examples of in-use airhouse failures. I felt like a doctor looking at the symptoms of an ailing patient. You need to find out the problem before you can know how to make it better.

This was when I first went to see Frei Otto at his Institute for Lightweight Structures in Stuttgart. I had read all of his books; he was clearly a genius. My heart was in my mouth on the university campus as I approached his astonishing building in the trees. I had seen pictures, but it was the most extraordinary place to experience. The cable net structure was clad in timber with a single mast lifting it into a draped conical form. It was actually the prototype structure for Frei’s West Germany’s pavilion at the Montreal Expo. I was really excited to get inside. Upon entering I immediately sensed an atmosphere of calm study and intense exploration. Young people all around were focused as nature guided them to discover a new way of designing buildings.

Frei Otto was charming, though a little scary. He was keen to help me plot a good route across Europe so that I could see the most interesting membrane structures and meet some of the most helpful people. While in Germany I went to Munich to see the Olympic Park and fell in love with the drama of the buildings. I remember the naked reality of the tension in the structural skin and the enormity of the masts and sweeping cables. It was impossible for me to understand how this could be imagined and built. I was hooked on the way that engineering could follow nature to drive such incredible designs.

While doing my research, I was involved in modelling a whole range of engineering projects with engineers from BuroHappold, all inspired by Frei Otto’s architecture. I learned a great deal through this, especially from Michael Dickson who often led the engineering. With cable net roofs in the US, in Canada, and in the UK, where we made models to explore forms with architects at the university, we were all learning together.

With such unconventional building shapes it was impossible to use normal building codes to define the wind loads on the roof structure. This is why we had developed a way to make the fabric models rigid using glass fibre and epoxy resin. I set up a wind tunnel at the university that would simulate the turbulence of real wind and put our rigid models in it. The tunnel allowed us to measure the wind pressures on the surface of the models. We would design accordingly.

This is how I started to understand structures. Every project was a leap into the unknown. Every solution was created from scratch. Your main tools were your brain and your engineering instincts. There were no codes or conventions to follow. If you felt your idea should work, you had to keep on thinking and testing until you proved you were right.

Now, I was learning things I never saw as an undergraduate. I could see I had made the right choice to join Ted’s research team. I could see that my imagination was going to be my most valuable asset, along with confidence. If you believe something will work, it’s only a matter of time before you prove it.

I gained my PhD in Air Supported Structures in 1983 and joined BuroHappold full-time as a structural engineer. I had experienced a very different apprenticeship at university than I could have found in practice. This gave me a head start; people seemed to assume that I was ready to be a designer.

During this time, I found myself working with clients in London and travelling very regularly about 100 miles in from Bath. These face-to-face meetings were essential to make good relationships. I enjoyed these meetings far more than being in the office. I started to realise how much I had been missing London while in the beautiful city of Bath. By 1994 I felt ready to get back to the capital, and I wanted to become closer with clients and architects. Mentioning this to Ted Happold, I was promptly sent to London. From this moment I found a great deal of freedom. It was my door to a treasure trove of design opportunities as we developed a new office for BuroHappold in the capital city.